Once upon a time, on the West Side of San Antonio, there was a small community known as Prospect Hill. It was a neighborhood of working families, local businesses, clapboard homes, a church and a parish school. Bordered by Colorado Street on the east, Zarzamora Street on the west, Martin Street on the north, and Guadalupe Street on the south, Prospect Hill was but one square mile in size. Everyone knew everyone else, and all was within walking distance.

Though no one knew it at the time, this modest and unassuming neighborhood would one day be known as the birthplace of many great San Antonio leaders.

Though its history reads like a fairy tale, Prospect Hill is very real, as are the amazing men and women who have called it home. One of the first communities built west of downtown in the early 20th century, Prospect Hill originally provided housing for working families associated with the railroad as well as many immigrant families from a variety of ethnic backgrounds who came to San Antonio in search of a safe and nurturing community to raise their families.

Throughout the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s, this humble neighborhood provided the sound foundation its children required to grow, learn and succeed and thus produced a generation of businessmen, artisans, civic leaders, military heroes and doctors, successful beyond expectation and dedicated to bettering themselves, the lives of their fellow men and women, and their community, as well as future generations.

So what made this particular square mile so different from every other square mile across San Antonio? I asked three men born and raised in this melting pot of acculturation and assimilation to share their memories of their beloved Prospect Hill. Through their wisdom and with their guidance, we will attempt to unearth the secrets of this nurturing neighborhood in hopes of recreating the foundation where many successful men and women were born.

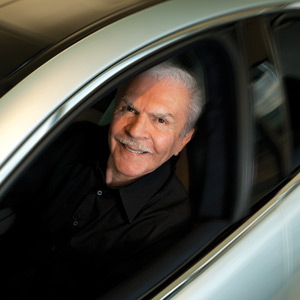

CHARLES T. BARRETT, JR.

For Charles T. Barrett, Jr., president and CEO of Barrett Holdings, an asset management company and authorized dealer for Jaguar, Ferrari, Maserati, Saab and Fisker, the road to success began at the front door of the family home on 3021 West Travis Street. His pride in his roots is evident, as is his fondness for his old neighborhood: “I am honored to be included in this group of men who grew up in Prospect Hill.” Barrett attributes much of his success to his loving family and the values they instilled in him as a child as well as the neighborhood environment that Prospect Hill provided.

Raised by his parents and a great aunt, Barrett and his sister learned the importance of responsibility from an early age. “In our home, accountability for your actions and respect for your peers, your subordinates, as well as respect for authority, were the most important lessons taught,” he recalls, “and treating others with dignity and respect.” Sacred Heart, the Catholic parish and parochial school attended by Barrett and many local children, further reinforced the importance of responsibility and respect. He recalls the significant role the Benedictine Sisters, who ran the school, played in his life. “At the time, they seemed larger than life and meaner than hell. They were very strict but very caring and loving. They taught us to respect authority, and I attribute much of our success to them,” he says.

Growing up in, as he describes, a “mixing bowl of ethnicities,” Barrett remembers the emphasis placed on one’s family heritage: “In Prospect Hill, people knew who they were and where they were from. Everybody knew where their parents were born, where their grandparents were born, where they came from, and why they were here. Pride in your heritage was very important, no matter what it was.”

Barrett’s father, Charles, Sr., was born in Monterrey, Mexico, to an American of British descent who worked for the railroad. As with many of the families who called Prospect Hill home, Barrett’s grandparents fled to San Antonio during the Mexican Revolution when the Mexican government expropriated the railroads and foreigners were not in favor. Charles Sr. was raised in San Antonio, graduated from Main Avenue High School, married and eventually moved his family to Prospect Hill. Barrett knows the story well. “Everybody knew and took pride in the sacrifices made for them to give them the opportunity to accomplish something,” he says. “And you always knew that you had a responsibility to others to give them the same chances that you had.”

According to Barrett, Prospect Hill was a community of close-knit families who looked out for each other’s kids. “Everything was within walking distance,” he recalls. Walter’s Drugstore, DeWinne’s Restaurant and the Malt House were a few of his favorite haunts. “All my friends lived close by, and we walked together to school every day. I never had to report home. If I misbehaved, I wasn’t sent home for punishment. Any one of the mothers in my neighborhood would reprimand me. And my mother did the same for my friends,” he says. In today’s world, where parents fear repercussions for punishing another’s child and the school’s authority to discipline has faded to near-nonexistent, this seems archaic and borderline risky behavior.

Yet Barrett attributes this co-parenting, shared-authority mentality as one of the major factors that set Prospect Hill apart. He explains, “There was no ‘Sammy’s mom says he can do this or that.’ Sammy’s mom and my mom were always on the same page. You never questioned whether something was right or wrong because all the parents felt the same way and supported one another’s decisions. There was no question as to who had the authority. All the parents had the authority to discipline.”

Though Barrett is now most often associated with luxurious high-line car franchises, including Jaguar and Ferrari, his first job was not so glamorous. “The first time I got paid for anything was when I got a job working for a neighbor delivering tortillas to little grocery stores around the area,” he recalls. He was 10 years old. Later jobs included sacking groceries at H-E-B, sweeping the parking lot of the local Handy Andy at the corner of Lexington and St. Mary’s and a variety of jobs at Hendricks Tire Company.

Barrett graduated from St. Mary’s University in 1962. Following a stint in the Coast Guard Reserves (he retired after 22 years as a commander), he went on to establish his own accounting firm before buying his first car dealership, a Jaguar and Ferrari store, in 1993. From there, more franchises were added, and his business grew. Today Barrett is an authorized dealer for Jaguar, Ferrari, Maserati, Saab and Fisker, and one of the most respected businessmen in San Antonio.

Throughout his life and career, Barrett has drawn from early lessons learned and looked for ways to give back to his community. “As a CPA, I served on six or seven national committees that were either for the benefit of small businessmen or for minority inclusion into the profession. I did a lot to bring awareness to the profession being more inviting to minorities,” he says. He currently serves as vice regent for the nonprofit group Rey Feo Consejo Educational Foundation and is a member of the St. Mary’s University Board of Trustees as well as chairman of the finance committee for St. Mary’s University.

Formerly, he served as president of the Fiesta Commission and was declared the 54th El Rey Feo (the people’s king) for collecting a record-breaking amount of money for the Rey Feo Scholarship Committee. He is also recognized by the Texas House of Representatives as an outstanding Texan for significant and lifelong contributions to the city of San Antonio.

One project Barrett is most proud of is the St. Mary’s Bell Tower Project that he initiated in 2006. “When I was able to financially do something for St. Mary’s, I wanted to do something that would draw students to the school by beautifying the campus,” he says. “St. Mary’s school song is The Bells of Saint Mary’s. Now, every day at 3 o’clock, the bell tower plays the school song.” The bell tower also serves as a memorial to his mother and son and is a reminder to all that good things come to those who give back. The bell tower was dedicated in February 2007.

LIONEL SOSA

As Barrett previously pointed out, the people of Prospect Hill knew their family heritage by heart. Lionel Sosa is no exception. Born in 1939 in the small family rooms off the back of his father’s dry cleaning business, Sosa worked alongside his family from a very early age. “My father learned the dry cleaning business from his parents, who had a home laundry service,” he says. “By the time my father was 21, he was ready to go out on his own. He chose Prospect Hill because it was primarily Anglo, and he knew that the Anglos had the money to get their clothes cleaned and laundered.”

Sosa remembers growing up in Prospect Hill with great fondness and recalls much of his life revolving around the family business. “I worked in the cleaners from the time I was 8 years old. All of us worked there. My father did not call it Sosa Cleaners but called it Prospect Hill Cleaners. I think that was his way of blending in. My parents were very proud of being Mexican, but they didn’t wear it on their chest,” he explains. Though many of the families of Prospect Hill, including Sosa’s grandparents, had fled Mexico during the Mexican Revolution, Sosa remembers the neighborhood as an ethnically mixed assortment of families. “Many of these families had come from Mexico, where they had worked on the railroad. There were lots of Germans, Belgians, Chinese and Lebanese. Growing up, most of my friends were Anglos,” he says.

According to Sosa, the ethnic diversity of Prospect Hill was a key factor in the success of the neighborhood: “I never considered myself different from anybody else. A lot of folks who grew up in my age felt discrimination, but mostly because they grew up in a segregated part of town. I think what set Prospect Hill apart was there was absolutely no entitlement mentality. We grew up in an ethnically diverse neighborhood where there was no discrimination. Everybody was everybody’s pal. And to my family, they were all friends and customers. Without a doubt, I think that growing up in a mixed neighborhood made all the difference in my life. I never felt like a victim, and I will never think of myself in that way. Nobody’s better than me, and I’m not better than anyone else.”

From the time he went to work for the family business, Sosa learned the importance of hard work and honesty. “In my family, the most important thing was that you worked for everything you had, and you were always 100-percent honest in all your dealings,” he says. By the age of 10, Sosa worked every afternoon from 3 to 7 and from 7 to 3 on Saturdays at the dry cleaners. “I was paid $1 per week,” he recalls. “My mother had a rule. Once you started working, you had to give back 50 percent of everything you made to the house. I had to pay her 50 cents per week! If I complained, she said, ‘These are the rules in this house. If you don’t like them, there’s the door.’”

At 13, Sosa rebelled, refusing to work any longer at the dry cleaners. “My mother said, ‘You don’t have to work here, but you do have to work.’ Then she got me a new job at Walter’s Drugstore. She could always find me a new job.” (According to Sosa, the 50-percent rule was still in effect.) This strong work ethic that he describes is consistent with many of the hard-working families of Prospect Hill, and is, it seems, a recurring factor in the success of its offspring.

The emphasis on hard work continued for Sosa throughout his years at Central Catholic High School. “As a Mexican kid, you were supposed to graduate from high school, get a job, get married, have children, work some more, then you die,” he says. “That’s what everyone did, so that’s what I did. College was never mentioned. In fact, going to college meant you were lazy and didn’t want to go to work!” It wasn’t until Sosa was several years into his first job, designing and painting signs for Texas Neon Sign Company, that he considered furthering his education. “I overheard a customer talking about The School of Personal Achievement. It was a 17-week course and cost $250.” Sosa procured a loan to take the course, then began working a second job on the weekends to pay it back. “The course said, ‘Whatever your mind can conceive and believe, you can achieve.’ I believed what it said and set the course of my life to those principles,” he says.

At age 26, with a wife and four children to support, Sosa began setting goals and working to achieve them: “I set my goals high. I wanted to open my own graphic arts studio, so I did it. I wanted to get into advertising, so I set a goal to be the largest ad agency in Texas in five years. I did it in three. And so on and so forth.” This strong work ethic, the belief in himself and his strong desire to succeed have served him well throughout his life.

In 1972, Sosa founded Sosa, Bromley, Aguilar & Associates (now Bromley Communications), the largest Hispanic advertising agency in the United States. He is also a nationally recognized portrait artist, author and speaker. In 2005, Hispanic Business magazine named him one of the 100 Most Influential Hispanics in the United States. Sosa has worked on numerous political campaigns, including the presidential campaigns of Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, George W. Bush and John McCain. He is currently the Hispanic media consultant for Newt Gingrich’s presidential campaign and is recognized as an expert in Hispanic consumer and voter behavior.

Sosa attributes much of his success to the strong foundation for life he received growing up in Prospect Hill. He explains, “The neighborhood had the old values: Be honest, work hard, be responsible, be kind. Hard work alone won’t do it. You have to have all the other qualities as well. And you have to feel a sense of gratitude for what life gives you.”

FERNANDO A. GUERRA, M.D., M.P.H.

Dr. Fernando Guerra’s maternal ancestors settled in the Rio Grande Valley in the 1800s as one of the land grant families. Like Barrett’s and Sosa’s ancestors, Dr. Guerra’s paternal grandparents fled Mexico when the danger and violence of the Mexican Revolution forced many families to seek asylum in the United States. Upon arriving here, the family settled in a small community in San Antonio that closely resembled the barrios of Mexico, where parents, grandparents, cousins and relatives all lived close by, not unlike the family compounds of Mexico.

“I was brought up in a very traditional Mexican-American family and household. Spanish was the first language. The family values of respect for our parents, grandparents and teachers, the importance of a moral value system, and also knowing that one has an obligation to one’s family and one’s community, were always stressed,” he says. Unlike many in Dr. Guerra’s generation, both of his parents were college educated, his father being the second Mexican-American to graduate from the College of Pharmacy at UT Austin. Following graduation, his father opened a pharmacy on the fringes of Prospect Hill and moved the family there when Dr. Guerra was in pre-school.

Dr. Guerra has come to consider his early introduction to Prospect Hill as an important part in a series of moves that took place in his family during his early years. “Prospect Hill provided a sense of upward mobility and also other opportunities in terms of community for our family,” he recalls. “It was an established neighborhood, it was settled. It provided families and friendships for my parents as well as for the children. I remember there was a pre-school run by some nuns that was very similar to the schools of Mexico, and it gave my parents an opportunity to stay connected with the Mexican culture and language of their past.” Indeed, Prospect Hill provided many families with the opportunity to establish a presence, find gainful employment and educate their children.

“Prospect Hill had some very important elements,” Dr. Guerra says. “It had a real sense of community in terms of support provided by families. There were still a lot of front porches where families gathered and kids came over to play.” He is quick to point out that it was the churches and the schools in Prospect Hill that provided the glue that held the community together: “In any community, the truly important institutions that provide a considerable presence in terms of relationships that a community develops are the churches and schools. When you have those in place, as Prospect Hill did, and if they are there to serve and support the community, I think that one really then has the opportunity to do good things.”

He also attributes much of Prospect Hill’s sound foundation to Sacred Heart Parish. “Prospect Hill was a real parish community. The religious sisters and the parish priests were very instrumental in creating a bond across families,” he says. “We all felt a part of the community; there were emotional bonds and ties between families. The families all wanted to see each other’s kids do well and succeed, and they shared in that responsibility. I think that is what is missing in today’s world. In my work, I see some very adverse outcomes in the communities that have lost that sense of a value system and the relationships between families.”

Dr. Guerra’s early interest in medicine stemmed in large part from time spent with his father at his pharmacies and watching him interact with patients. “My father’s pharmacies were established in a very traditional barrio-type setting where people would come to get advice or medicine. He provided clinic space within the pharmacy for physicians to serve patients on a walk-in basis. I learned early on that it was possible, with training and experience, to serve a community in a way that was beneficial,” he says. He describes his father’s pharmacies as an early model for him in the work that he did with community health centers. Indeed, Dr. Guerra, as his father before him, has been an advocate for the under-resourced communities of San Antonio.

Dr. Guerra also recalls his mother being hugely influential in steering his career along the path of service. “My mother really served as an important role model through her activities as a volunteer,” he says. “Her work gave me some terms of reference as to what the needs were in the community.”

The importance of education was always a large part of Dr. Guerra’s upbringing, reinforced by his parents, the Benedictine Sisters of Sacred Heart and other teachers along the way. He earned his medical degree from the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston and his Master of Public Health degree from the Harvard University School of Public Health, where he has received the Alumni Merit Award. Early in his pediatric training, he was called to active duty and served our country as a battalion surgeon with the 10th Combat Aviation Battalion in Vietnam. Among his decorations was a Bronze Star. Though his list of accomplishments is long and prestigious, he recalls with fondness the very first community health center he set up during his early years as a doctor, deep in the heart of San Antonio’s West Side.

Dr. Guerra recently retired as director of health for the San Antonio Metropolitan Health District after 23 years of service. During his tenure, he oversaw the operation of 32 health care facilities across San Antonio. He instituted improvements in the immunization program, expanded the WIC program, established the Public Center for Environmental Health and also Project Worth. He was elected to the Institute of Medicine and also to the Academy of Medicine, Science and Engineering of Texas.

Currently, Dr. Guerra serves as a consultant to the City of San Antonio in public health and health policy and also practices pediatrics. He is a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas Health Science Center and serves as an adjunct professor in public health at the Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine at Brooks Air Force Base and the University of Texas School of Public Health in Houston.

It is clear that the Prospect Hill of old was a neighborhood that provided a sound foundation for hard-working families to raise their children. From these men, I have gleaned the importance of an engaged and supportive family, an emphasis on responsibility, accountability, hard work and education, pride in one’s heritage, a strong and dedicated school system that reinforces values instituted in the home, the support of a local church and a close-knit community of families working together for the betterment of all. For it was these elements that provided the right mix of circumstances in Prospect Hill that encouraged great things from so many of its children.

A Partial List of Former Prospect Hill Residents You Might Recognize:

Hope Andrade — Commissioner for the Texas Transportation Commission

Alex Briseno — Retired San Antonio city manager and professor of public service at St. Mary’s University

Carol Burnett — Actress

Henry Cisneros — Former mayor of San Antonio, founder and chairman of American Sunrise

Ruben, George and David Cortez — Owners and managers of the family restaurant businesses, including Mi Tierra, Pico de Gallo and La Margarita

Tessa Martinez Pollack — President of Our Lady of the Lake University

Dr. Ricardo Romo — President of UTSA

Jesse Treviño — Nationally recognized artist

Maj. Gen. Alfred Valenzuela (Ret.) — Major General, U.S. Army, retired